Project Description

During World War I and World War II, army and navy fortifications and artillery pieces surrounded Narragansett Bay, but no shots were ever fired in anger. By contrast, from 1929 to 1933 during Prohibition, Coast Guard vessels in Narragansett Bay and other Rhode Island waters fired thousands of machine gun and one-pound cannon rounds. . . at fellow-Americans.

The intended targets were crew members on rumrunners who, using speedy powerboats, had picked up illegal liquor from supply ships stationed at “Rum Row”—an area beyond the twelve-mile zone off the coast of southern New England and Long Island. The rumrunners, operating at night or in foggy conditions, on their return voyages would cruise up Narragansett Bay to assigned drop off points to unload their liquor. Because buying and selling alcohol was illegal under Prohibition laws then in force, the profits from a successful voyage could be enormous.

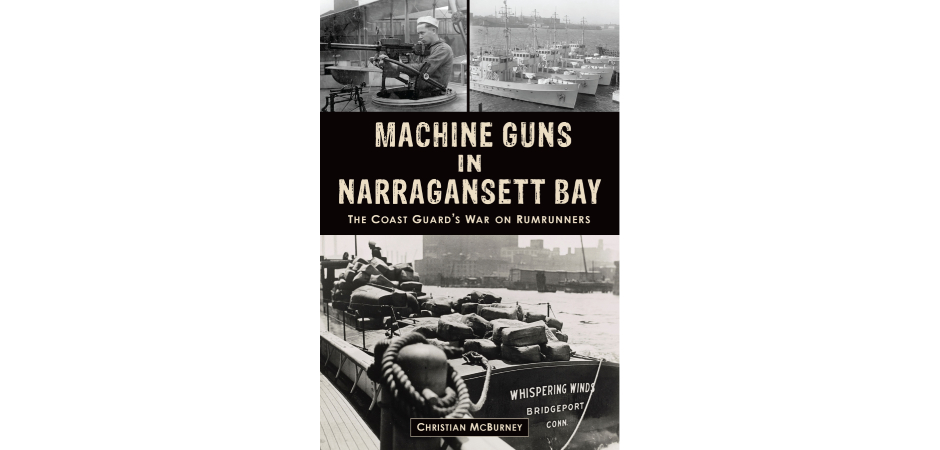

The Coast Guard became the lead federal government agency fighting the “Rum War” at sea. Coast Guard patrol boats insisted on inspecting vessels suspected of carrying illicit liquor, and if they did not stop after being signaled, they were targeted with live ammunition from large caliber weapons—machine guns or one-pounder cannon.

Sometimes the extraordinary one-sided “battles” were witnessed by Rhode Islanders from the shore. For example, in October 1930, a veteran of World War I, from his house at Watch Hill, told a Providence Journal reporter about the Coast Guard’s attack on the rumrunner Helen off nearby Napatree Beach: “I could see the flash of the one-pounder and I think they [the Coast Guard patrol boats] must have fired it 50 times. Searchlights were flashing along the beach and the reports of the one-pounder and the rat-tat-tat of machine-guns sounded like a battle. . . . I told my wife and daughter to get away from the window.”

The Coast Guard was in a difficult position. It had the duty of enforcing federal laws at sea within the waters of the U.S. and it did not want lawbreakers to escape simply because they used speedboats. If the Coast Guard had been dealing primarily with speedboats that were illegally importing harmful drugs such as heroin or opium, then having their patrol boats fire machine guns at the fleeing speedboats would not have been particularly controversial. But that was not what was happening during the Prohibition years from 1920 to 1933. Drinking alcohol recreationally remained wildly popular among wide swaths of the population in the United States, particularly in northeastern states, especially Rhode Island. Even many public officials—governors, mayors, attorneys general—drank bootleg liquor.

Moreover, the crews on the rumrunners typically were not hardened criminals. Many of them were former struggling fishermen or ordinary young laborers, first and second generation immigrants and otherwise good people, who during the desperate years of the Great Depression saw rumrunning as a chance for making a quick buck. Thus, having Coast Guard vessels fire their machine guns at rumrunners became a controversial practice.

My book examines the incidents in which Coast Guard vessels fired large caliber weapons—Lewis machine guns and Hotchkiss one-pounder cannon—at and into fleeing rumrunners in Narragansett Bay and in or near other Rhode Island waters from 1929 to 1933. The source material is primarily the Coast Guard’s own records and contemporary newspaper articles.

In the incidents covered in the following pages, three crew members on rumrunners were killed by machine-gun fire; one drowned after his boat was machine gunned, caught fire and exploded; another fell off his boat and drowned in mysterious circumstances after his boat was chased and fired at; two others suffered serious, life-threatening bullet wounds; and eight more received minor or moderate bullet wounds.

I have come up a total of 29 shooting incidents in which the Coast Guard fired large caliber guns at rumrunners, striking the craft, in or near Rhode Island waters. In several incidents, hundreds of machine gun bullets were fired. It is a wonder that more men were not killed and wounded.

One Coast Guard officer and his patrol boat will be mentioned more than any others in the book—Boatswain Alexander C. Cornell and CG-290. While in command of this vessel, Cornell ordered the firing of a machine gun at the fleeing Black Duck, resulting in the killing of three crew members and the wounding of its captain. Cornell, usually commanding CG-290, opened up his machine gun in Rhode Island waters on five other rumrunners: High Strung, Helen, Idle Hour, Mitzi, and Yvette June. In the incident involving the last vessel, the machine gun bullets and one-pounder shells fired by Cornell’s patrol boat caused Yvette June to explode, killing a crew member. Thus, one aggressive Coast Guard officer was responsible for the most violent and deadly episodes in Narragansett Bay. Still, his superiors at New London’s Section Base 4 praised his tenacity in bringing rumrunners to heel and enforcing the laws. Other Coast Guard officers began to imitate Cornell, such as Elsworth Lathan based in Newport, Cecil MacLeod based in Woods Hole, Massachusetts, and Theodore Losch stationed at New London, Connecticut.

In one sense, the Coast Guard officers and crews ordered to enforce Prohibition were not to blame. The Coast Guard was part of the Treasury Department. Most of any blame was due to Coast Guard and Treasury Department policies that authorized Coast Guardsmen to employ large caliber weapons to shoot at fleeing vessels trying to avoid inspection. The intent was not to kill crewmembers aboard rumrunners. But when those strict “law-and-order” policies intersected with the wildly unpopular Prohibition law and the demand for illicit liquor, accidents leading to tragedies inevitably occurred.

On three occasions in federal district court in Providence, federal judges lambasted the Coast Guard for shooting at fleeing rumrunners. On one of those occasions in March 1932, U.S. District Court Judge Ira Lloyd Letts, at the trial of the Rhode Island rumrunner Eaglet, called Coast Guard patrol boats firing 470 machine gun bullets in Narragansett Bay at Eaglet “a rather sad commentary on the administration of law in this country.”

My book also shows that many Coast Guard patrol boat commanders failed to follow the federal statutory requirement for a gun to be fired as a signal, and the Coast Guard policy requiring three blank one-pounder shells be fired as signals, before any machine gun bullets or live one-pounder shells could be fired at a fleeing vessel. In addition, noncompliance with these rules rarely had any consequences. The Coast Guard also had rules requiring Coast Guardsmen firing weapons to be careful not to endanger the lives of innocent persons onshore, but the rules were so vague as to be almost useless guidance.

Another interesting aspect of the incidents described in the following pages is that Coast Guard patrol boat commanders and their superiors were, too frequently, not truthful when it came to explaining the circumstances to the public surrounding the shooting of live ammunition from large caliber guns at rumrunners.

How to Purchase:

These outlets currently have Machine Guns in Narragansett Bay in stock (more are expected soon):

Southern Rhode Island:

Wakefield Books, Wakefield Mall (many copies in stock)

Picture This, Wakefield

Island Bound Bookstore, Block Island, Water Street

Newport and Aquidneck Island:

Charter Books, Newport, 8 Broadway (just north of the Old State House)

Commonwealth Books, Newport, 29 Touro Street

Island Books, Middletown, Wyatt Square, 575 E. Main Road

Newport Historical Society Gift Shop, Newport, 127 Thames Street (Brick Market building)

Northern Rhode Island:

Brown University Bookstore, Thayer Street, Providence